Architecture for the Needs of the Hearing Impaired

"Please step away from the closing doors!" and "Hello, can you hear me?" Our world is predominantly designed for hearing individuals, yet it also accommodates millions of deaf and hard-of-hearing people. How would our environment change if it were tailored to meet their needs?

Donatas Pocesiunas

5/8/20241 min read

Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., a premier institution for the deaf and hard of hearing, has been at the forefront of reimagining architectural spaces. Entire buildings are being redesigned to create sensory experiences for those who cannot hear. In collaboration with architect Professor Hansel Bauman, Gallaudet embarked on an ambitious project to explore how buildings, campuses, and even entire cities can include spaces specifically for the deaf, considering the unique ways they perceive and interact with their surroundings.

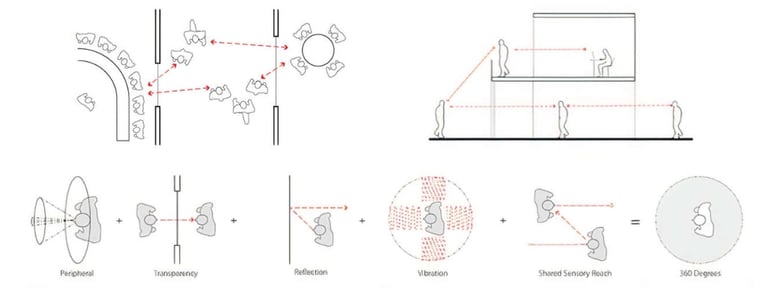

One innovative approach involves arranging lecture halls in semicircles or U-shapes, enabling students to maintain constant visual contact with their peers. This setup facilitates engagement in discussions, ensuring clear visibility for everyone. Wider corridors and staircases are crucial for those communicating in sign language, respecting specific distance parameters and enabling observation of full-body gestures. Ramps, preferred over stairs, ensure continuous visual communication without the need to look down.

Visual cues are essential for the deaf to navigate spaces, making a clearly visible environment vital. Features like glass elevators and transparent or frosted doors help individuals see if someone is approaching or has entered a room.

Color schemes and thoughtful lighting are pivotal in enhancing communication accessibility. Well-designed lighting ensures that facial expressions and hand movements are easily visible, crucial for sign language users.

Mirrors also hold significant importance in deaf-friendly spaces, offering the ability to see behind and detect approaching individuals, enhancing awareness and security.

Designing for the hearing impaired goes beyond mere compliance; it involves creating inclusive environments that foster communication, safety, and a sense of belonging. As we push the boundaries of architectural design, it's crucial to consider how our built environments can serve all members of society. Gallaudet University and Professor Hansel Bauman's work stand as inspiring examples of what can be achieved when designing with empathy and inclusivity at the forefront.

For a deeper understanding of these principles in architectural practice, explore the 'DeafSpace Design Guidelines' document. It offers detailed insights and practical recommendations for designing inclusive environments. You can access the document here to delve into DeafSpace principles and their application.

https://www.scribd.com/document/605705695/Deafspace-Design-Guidelines